A look back at looking forward: Disruptive technology throughout history

Nevin Carr is a Leidos Vice President and the company’s Navy Strategic Account Executive. Carr enjoyed a 34-year Navy career, culminating in the role of Chief of Naval Research where he led 4,000 scientists and engineers in executing the Navy’s $2 billion science and technology efforts. Here are some of Carr’s thoughts on disruptive technology, its importance to the Armed Forces, and how Leidos approaches innovation.

Can you give us an overview of the development of disruptive technology and how it’s been perceived among the Armed Forces historically?

The Department of Defense is pretty risk averse when it comes to the technologies that they want to use for war fighting, and that's the way we want it. We don't want them to take a lot of risk when that risk might mean putting our soldiers and sailors at risk. In a perfect world, we'd like to know with 100 percent certainty that everything works. And we'd like it cheap and we'd like it quick. In reality, it doesn't work that way, every decision is a risk management decision.

If you go back to 1962, the U.S. Government was funding about $3 out of every $4 of research. If you track that data through today, it's almost linear, we've [government and industry] almost traded places. If you picture a graph in your head, it's like a great big X. The U.S. Government portion of funded R&D has gone down to about $2.50 today.

Industry – in other words market-driven R&D – now performs the vast majority of research in this country. This is the opposite of the way it’s been done throughout history. In 1969, government went to industry and said, “Here’s a pot of money, help me get to the moon.” You can track that conversation all the way back to innovations like siege engines to knock down castles, warships in the 1500s and 1600s, the invention of gunpowder, and cannons. Government has typically leaned in more with developing technology. All that was driven by the number one imperative in countries throughout history and that was for the country to survive, to not get taken over.

In the last 30 years, that’s really been flipped on its head. And so if you look at today, technology doesn't flow from government investment to civilian use. Aviation became what it is because of Defense Department investment. Radar was adapted from microwave ovens. What we know as GPS today came out of the Navy Research Lab. Radios and IT technology all came largely from Defense Department or government investment. Those were the old days, when the government had its hand on the throttle of what was being researched, developed, and discovered.

So what’s different today?

We've traded places and it’s the market that’s driving technology development. The government’s not driving that train and, in many cases, isn’t even a major passenger. Industry isn't developing iPhones for a government customer.

By the way, this is a very healthy evolution for a true free-market economy. The market should be the driving force, as it is today, and I’d argue that is one of the reasons we are seeing such an explosion in innovation and, as a result, prosperity. But the government, Defense Department, and the Armed Forces have to adapt. They have to become fast followers for the first time. Now, as to why we’re even having this conversation about emerging and disrupting technologies, it's not because we want to, it's because we have to.

It's because technology is moving at a faster and faster pace — it's beyond government control and it's not necessarily responsive to what government wants. We have to respond to where it goes based on market demand. We have to buy chips from chipmakers, we have to adapt computers, and we have to push our IT to the cloud because that's where the market is going.

It's a different mindset on how you keep up in a defense environment so that your weapons and your systems will be the best in the world to defend the country and protect our interests. We have to use technology in some cases, in many cases, that we don’t directly control. That's pretty huge.

The rate of technological change is so rapid, I doubt anybody reading this article still has an iPhone 1; yet they didn't even exist just a few years ago. The game isn’t about inventing a perfect single-point solution that's going to last for 20 years; it's about designing and building systems that can adapt and keep up in stride with a threat that we can't predict, using technology that we don't control.

How do both government and industry react to this new playing field?

It pushes you to a place where you have to leverage the potential power of what disruptor technologies, like iPhones and mobile apps, can do. How do we use these advancements in a military context, in a military environment, and still protect the country and the Armed Forces? The very notion of using a disruptive technology means you've allowed the risk equation to change a little bit, and that's not an easy to decision to make.

What are some of the challenges government and the Armed Forces face when using disruptive technologies to counter emerging threats?

Unquestionably, one of the greatest obstacles we face in doing what I just described — keeping up with this rapidly changing future — is how we acquire disruptive technology. I don't say that to demean the people who do that; they're dedicated, hardworking people that are coming to work every single day to try and acquire and put together the systems that will give our war fighters the tools they need. But they live within a very bureaucratic, very difficult process that is really designed more around the government-funded side of the R&D curve. If you look at a company like Eastman Kodak — that failed to adapt to the disruptive change that came from digital photography — just 15 years ago, they sold something like 85 percent of the world's photographic paper. They’re bankrupt today, they're gone. They don't exist. It can happen that fast.

It's a very unforgiving environment and it's not about perfect point solutions, it’s about adapting in stride. It's not about being the biggest or the strongest, it's about adapting. That's why sharks and cockroaches are around today. Wooly mammoths? Not so much. Tyrannosaurus Rex? Gone.

What does Leidos do specifically to make the company and the technology that it develops able to adapt to these needs?

One of the things we do is really something we don't do. We’re not an OEM — an original equipment manufacturer. We don't build ships and tanks and planes, and therefore we're not trying to sell the government or customers our ships or our tanks or our planes. That’s because when you do those things, they take a long time to develop. They take decades and then there are long, long procurement streams, and that's not what we're about at Leidos. We're much more agile than that. We look at a platform and envision the open architecture that the platform needs to keep up with an ever-evolving threat. Maritime autonomy is a perfect example. It's a disruptive platform in its own right.

And because autonomous systems are disruptive, the Department of Defense is leaning very far forward. They see the potential and they understand that it’s part of the future of warfare, and they're looking to companies like Leidos to make those systems. We're not going to flip a switch and suddenly have an all-robotic future; we're going to have a long period of overlap where these things have to work together. So they're looking to companies like us to help not only in the near-term — when newer systems have to work alongside older systems – but also to help get to that autonomous future.

One of the important elements is open architecture. We have to build around open systems that will be adaptable over time.

What kind of culture, environment or team needs to be in place to drive the creation of disruptive technology?

There are a few things in these areas that set Leidos apart. We're agile, were entrepreneurial, we like to think differently, and that's why we came up with the design we did for Sea Hunter. It was the only entry that came in with a trimaran hull. All the others came in with a semi-submersible hull.

We were able to show that we had done the modeling and the simulation to justify the design and the concept. We had done the intellectual heavy lifting that led us to the design that met the distance and stability requirements. We were able to win the day because of a strong data-driven argument.

If you had to pick something from the past, as a disruptive military technology, what would you pick?

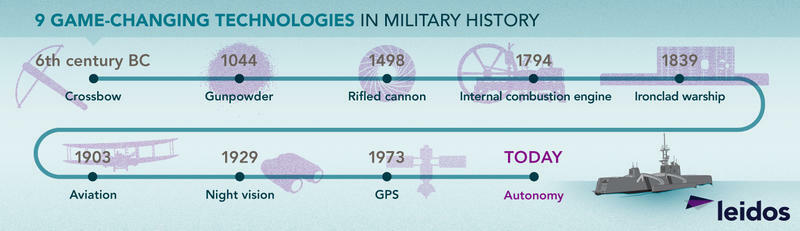

Well, you almost have to pick a window of time. Certainly it began with the first person that learned to sharpen flint and make a spear point that was more effective than a stick. I would say the crossbow is certainly right in there, to the point that it was banned by the church because it could penetrate armor and kill knights. Gunpowder in the more modern era, and you can look to the Civil War for some major disruptive technology when it came to ironclad warships. Aviation was obviously huge.

I think we’re at a point where autonomy is going to be every bit as impactful to the future of warfare as aviation was 100 years ago.

Do you see the R&D curve tilting back in government's favor ever again? If not, then how can the government and industry work more closely to produce advances to counter emerging threats?

No, I don't see this ever going back. I think this is a forever shift and governments looking forward are going to have to get better and better and quicker and quicker and more agile to keep up with technologies they do not control, and use them in ways that are still evolving.

There will always be important things that the military will want to maintain very close control over, but it's I think more and more falling on the government's shoulders to understand and keep up with technologies that are being driven by the market and build their systems in such a way that they can evolve these technologies affordably and in stride.

Can you talk to us a little about the company’s role in the Emerging and Disruptive Technology Essay Contest?

We like to be associated with emerging and disruptive technologies, so we started sponsoring this essay contest. This is our second year in partnership with the U.S. Naval Institute.

The first year that we did it we had more than 200 entries, which was a record for the Naval Institute for a first-ever essay contest. We followed up with almost 140 entries this year, so over two years we've had about 350 people that cared enough about the subject to take significant time and write an essay about disruptive technology. I wish we could give every single one a prize but we had to pick three essays out of all the entries. Many of those submissions are from young military officers and civilian scientists that work for the Navy, so we feel it's very important to be part of supporting this conversation and we're interested in what they have to say.