This engineer's work could be one giant leap for RF imaging from outer space

This spring, Leidos Principal Signal Processing Engineer John Kendra was named a 2018 NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) Fellow. One of only 25 fellows, Dr. Kendra's approved research proposal is on the concept of "Rotary motion-extended array synthesis." Phase I grant funding for his research is valued at approximately $125,000.

Dr. Kendra has a bachelor's degree in electrical engineering from the University of Houston and master's and doctorate degrees in electrical engineering from the University of Michigan. He lives and works in Northern Virginia.

We recently interviewed Dr. Kendra about his work and a condensed version of our conversation is below.

Congratulations on being named a NIAC Fellow!

Thank you!

If everything goes well, could your research eventually earn a Phase II award?

Oh, sure. In fact, the odds are pretty good. I looked at the historical performance statistics. It looks like around 40% go on to Phase II. And that's a somewhat larger program — at a certain point, the sky is the limit if NASA decides to actually build a system based on your concept. These can be billion-dollar systems.

So what do you tell people when they ask what you do for a living?

Normally I say engineer, and that's about as far as most people want to go [laughs]. If they want to know more than that, I’ve come up with a pretty good description. I say I do remote sensing, which has three components that I work on. You have a phenomenology aspect: what is the thing that you want to sense? What can be sensed to inform whatever you're interested in? The second part is, what kind of sensor concept can you imagine, or define, that would be able to collect on that phenomenology? Whether from space, or airborne, or something like that. The third part is processing of the data. Once this collection system has collected these observations in the form of data, what is the processing, or algorithms that have to be applied to it, to extract the information we want? Those three aspects of remote sensing pretty much comprise what I've done my entire career.

Have you worked with NASA before?

I've done a little work with NASA. As a graduate student, I had a project with NASA that involved detecting and measuring ice formation on the material, at the time, that coated the external fuel tank of a space shuttle. You may recall there was a problem with ice production. Our project utilized a radiometer in a remote sensing technique to, from a distance, detect the presence of ice, and actually measure how thick it was.

NASA says that all of the fellows' ideas have "the potential to transform future human and robotic exploration missions, introduce new exploration capabilities, and significantly improve current approaches to building and operating aerospace systems." What does praise like that from NASA, and this recognition in general, mean to you?

It means a great deal. These are some fairly new concepts that we've come up with. The basis for this project is a body of work that we published last year; it's a set of three papers, which is this MXAS, or motion-extended array synthesis, idea. It's a fundamental framework of theory and methods looking at this topic.

The Rotary MXAS idea is one concept that flowed out of that work. We’ve detected some reluctance from some of our traditional customers to invest in this because it's a new idea and not well understood. I'm very grateful to NASA because they have a reputation, and it's well-deserved, for doing cutting-edge, very innovative things. So it kind of makes sense that they would be the ones who would first recognize the potential.

And it is potential at this point because we don't know if it's going to work. It is, I think, quite an interesting idea, and we're very much gratified to do this, receive that award and the opportunity to pursue this research.

How would you explain the concept of rotary motion-extended array synthesis to a general audience?

It can be a challenge [laughs]. It depends exactly what the level of curiosity a person really has. I've explained it to my mother.

Did she get it?

She's not an engineer, but I think she got it. I can't really resist the temptation to give a little technical background. The starting point is the recognition that the larger an aperture is, the better you can see. People are most familiar with this with large telescopes, optical telescopes. The larger the telescope, the greater the spatial resolution, that is, the finer the angular resolution. This is the idea; and mankind has had a historical quest, for at least the last century, in which people have tried to build larger and larger effective apertures. It's not always in the optical realm, although it includes optical, but also RF [radio frequency]. Radio astronomy is a great example, where people have tried to come up with these concepts for building these larger effective apertures, that can deliver large aperture performance, but without being infeasible to construct because they're so large.

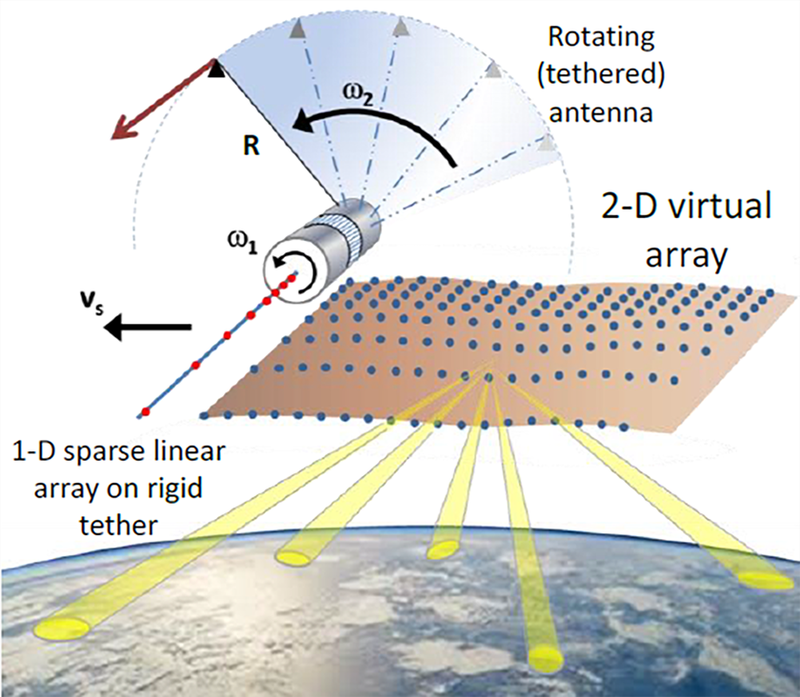

MXAS, which underlies the Rotary MXAS concept, as I explained a little earlier, is the idea that you can construct an effective aperture using the differential motion between two or more separate sensors. That implies they're moving and, sort of in the space that is swept out by the differential motion of these sensors, you have an effective aperture. The disadvantage of that concept is that's a fleeting phenomenon; these things would eventually move too far away from each other, causing it to be a one-time creation of this effective aperture.

Rotary MXAS is an idea by which you can continuously recreate this effective RF aperture by these separate sensors moving relative to each other, the rotary one versus the static one, and to create a staring or persistent capability, which should be very useful.

Were you doing signal processing engineering right from the start of your career, and one thing has just led to another?

Yes. Out of school, I was with Raytheon for 12 years and now I've been with Leidos for 10 years. As I look back on it now, it really does feel like all of my professional experiences and my education have really reinforced themselves to create a pretty good domain of knowledge. I think it's human nature for all of us to impart some coherence on our own personal narratives. I think that's human nature, and I'm sure I'm doing that too, but it really does feel that way. It's a good feeling, that nothing has been wasted.

We recently did a proposal that was for a large space system, a remote sensing system. I was the technical lead on that, and I was struck by the level of domain knowledge, the expertise, I suppose, I have acquired that allows me to take a major role in designing solutions like this, that I wouldn't have been able to do 5 or 15 years ago. I do have that feeling, that things have really reinforced themselves and brought me to this state.

What does the funding and support from NASA mean for your research?

It's modest for the standards of the work we do, but it carries prestige for sure. They're very competitive; a lot of people know about it. It means a great deal and it's recognition of these ideas, which are innovative. It's going to allow us, hopefully, to demonstrate the feasibility of these ideas, that they can perform like we intend for them to perform.

What’s going to be the nature of the research?

We'll be doing high-fidelity simulation, with computer models, and math models. We can, very realistically, recreate, or predict at least, through signal processing, and mathematical and geometrical modeling, how this is likely to perform. In addition, we'll be looking at the system aspects of it. Can you realistically create these systems? This will involve a spinning tether. We have people that we work with, companies that are teammates of ours, that are in the business of putting up innovative payloads in the form of SmallSats [small spacecraft; mass less than 180kg].

That would, very likely, be the next phase of this, to consider building a very small scale model of this to operate in LEO — low Earth orbit — that would involve a tether just a few meters long. Just to demonstrate the principles and, if that worked, it could be massively scaled up.

That could be Phase II, potentially?

Potentially, Phase II could have a hardware, and even a space component. Nowadays, with what's being done with SmallSats, it's becoming quite a commodity.

Have you had a chance to look at the research the other Phase I fellows are doing? Anything catch your eye?

[Laughs] Yes, there's a spectrum of wild ideas there. I feel like mine is probably on the less wild end of that spectrum, which I don't have a problem with. I kind of think that it possibly increases the chances that we will go on with this project, because I think it’s very feasible to do what we're doing. Some of these are quite way out ideas. The swarm of flapping robots, I think, was an interesting one. And I don't mean to disparage them at all. I think it's great, as we talked about earlier, for NASA to think big, and think into the future. Twenty, 30 years from now, what could be done? I would say, on that spectrum, ours was probably just wild enough to make the cut [laughs].

Who are some of your inspirations or mentors? Is there anyone famous, or otherwise, who’s played an important role in your career?

Thank you for this question… it’s a really interesting one for me because, honestly, I've never really been one prone to hero worship or anything like that. I've never really been one to identify individuals in my life that I particularly wanted to emulate. You might call it role models. Maybe I'm a little unusual, in this respect. I don't feel I've really had those, per se.

I've always been struck by the fact of our humanity, and that people are very imperfect. People do things well, but nobody does everything well. That’s not to say that I'm not inspired; I'm inspired all the time by people I work with, on a weekly basis. I'm inspired by historical figures, and major figures. That's what intrigues me; that, in our endeavors and our explorations, there is this struggle, and there's this fumbling around. People make mistakes, people doubt themselves. Those are the kinds of stories I enjoy.

There are a few books I can think of that reflect this. There's a book called Quantum, which recounts how Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr debated and argued about the nature of reality and quantum physics. It's very interesting how, occasionally, one of them would get the upper hand on the other, and just cast the other into tremendous doubt. I have always appreciated this idea; that even the greatest among us still had these doubts and struggles, and some go on and fail. That's one example.

A couple other ones ... I recently read the book The Enigma about Alan Turing. Another very imperfect individual who accomplished great things. You can also find this sort of thing in Richard Rhodes’ great book, The Making of The Atomic Bomb. It’s a complete account of the scientific exploration, and the notion that all of the things that we do that are great are the sum of a lot of little separate contributions, successes and failures.

Quite an honest and fascinating answer to that question, thanks for sharing that.

Ultimately, you can only be yourself, and you've got to figure out a way to make of yourself your best self. I want to also add that I have two adult sons and I've never seen fit to instruct them, or tell them how they should run their lives, or what they should do. When you take into account all the different interests, and opportunities, and circumstances, I just don't see how one person can reasonably tell another person that you should run your life in some particular way.

Can you tell us about some of your hobbies or interests? What do you like to do?

Running is a big interest of mine. I'm a decent marathoner, a 3:05-ish marathoner. I ran Marine Corps last year; I'm doing Chicago this year. I'm with the Washington Running Club, and I've been into running for pretty much my whole life. I took up skiing about 10 years ago, and I'm passionate about downhill skiing now. I'd recommend the Ski Club of Washington, D.C. for anyone; they sponsor a bunch of trips every year, and that's something that we've been doing.

I've always been a big reader, both non-fiction and fiction. I recently read the works of David Foster Wallace and I highly recommend them. You might want to start with his short stories before you get into his tomes!

And I enjoy traveling with my wife. Then, the usual leisure activities, this being the golden age of TV and everything. There's plenty to do to fill my very abundant free time [sarcasm], because, as you know, we all work really hard.

We hear a lot about the private space race that’s happening now. There are a lot of companies that are involved and heavily invested. Do you have any thoughts on that topic?

I'm not a student of the topic but I'm supportive of the idea that market forces are driving this, and I think that's a good thing. They're showing what is an effective approach to introduce innovation, especially apart from the human space flight aspect — which is not on the ticket for these guys right now — and they're able to do things very fast.

Another aspect of that is the great proliferation of CubeSats [a miniaturized satellite for space research] and SmallSats being launched for all sorts of purposes. That's making things really exciting for our industry. In fact, we're starting to get into a lot of these types of things. Frankly, these MXAS ideas have a play here also because, it's one thing to put SmallSats and CubeSats up into space. But, I think what people are beginning to recognize is, you also have to have some innovative things that the satellites are going to do when they're up there.

We're past the point of appreciating the novelty of putting CubeSats and SmallSats into orbit. Now, it's like, ‘OK great, but what are they going to do for us?’ That's where it also becomes interdisciplinary. What’s exciting now is that, people like me, and people in this building, are getting an opportunity to provide part of the space solution, whereas we really would not have before. Now, we're in a position where we can provide part of the solution, with our sensor concepts, our signal processing concepts, aperture synthesis concepts. And it’s a part of the solution which is not a small part, but instead could be the major part. It’s a very exciting time right now. We're thinking that in these next few years, we’re going to have some real opportunities to do something in space. It's opening up that field to a lot of people.

There are also these debates that seem to pop up every now and then about NASA's funding and the agency's direction, what it should focus on, etc. Any opinions on that?

I do have a couple thoughts. One is, I never cease to be amazed that, in the world we live in, the country we live in, that we still manage to fund, to the tune of some pretty big numbers, some really quite esoteric space missions. Missions with billion-dollar satellites, doing things that, quite frankly, even I, as a fairly educated technical person, have very little understanding of. They're exploring phenomenology, and I don't always understand it, but I think it’s amazing that we fund these things, and I’m gratified, quite frankly, that we, as a people, are taking the long view. If there's anything I believe, it's the value of understanding things at their most fundamental level. When you understand things at their most fundamental level, you have the ability –

this is the engineer in me talking – to do something with those building blocks, to engineer new solutions the world has never seen. I hope they continue to do those things.

Philosophically, I very much support the idea that the best products of our human intellect incrementally build upon one another for the betterment of the world and humanity. I know that the direction, on short time scales, can get steered here and there; but, fortunately, in part because these projects are so big, and they take so many years to develop, they acquire a momentum that can't be easily stopped.